Basic details: 2-4 players; 20-60 minutes; competitive

Dates played: November 21 and 22, 2020

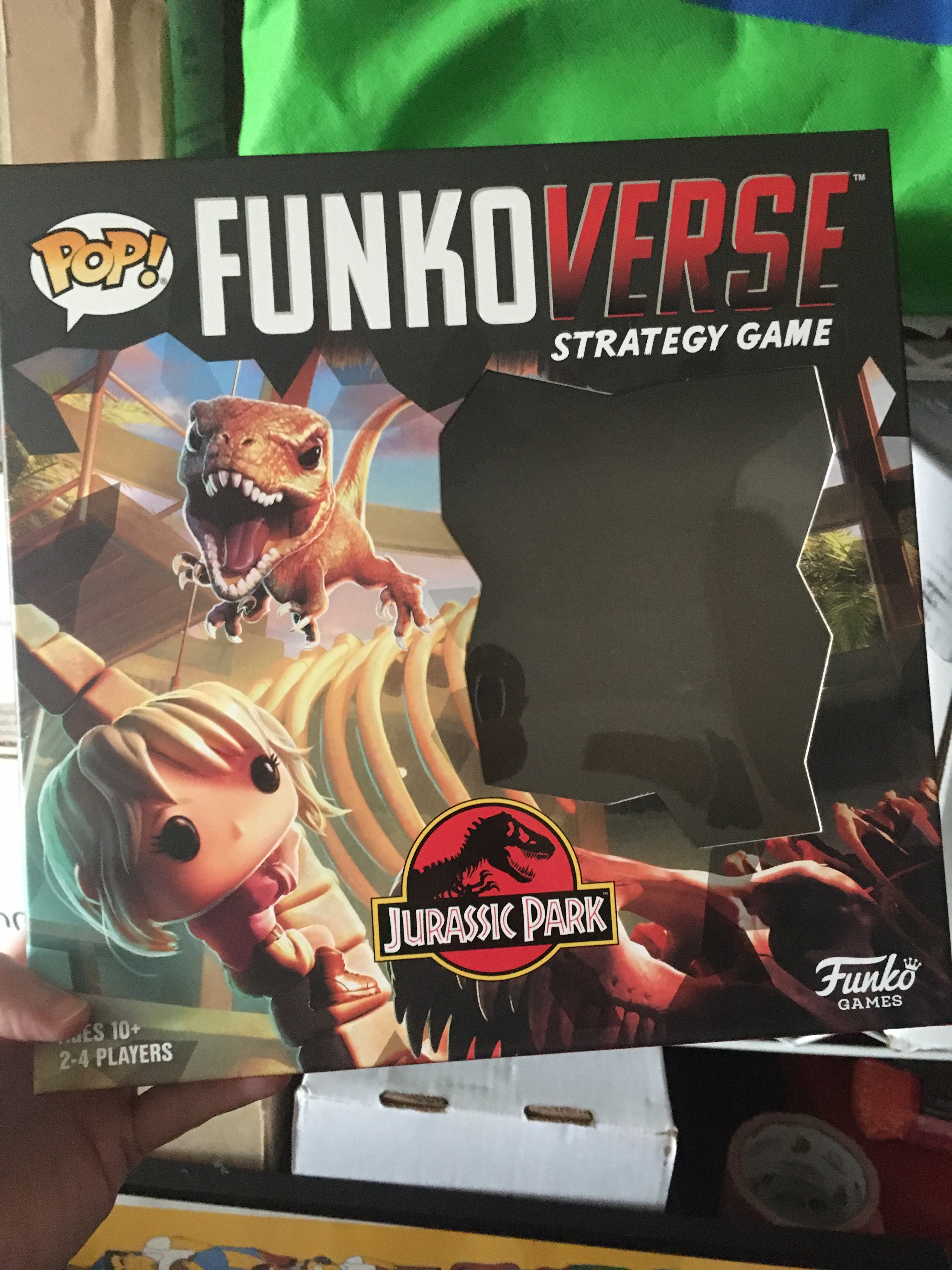

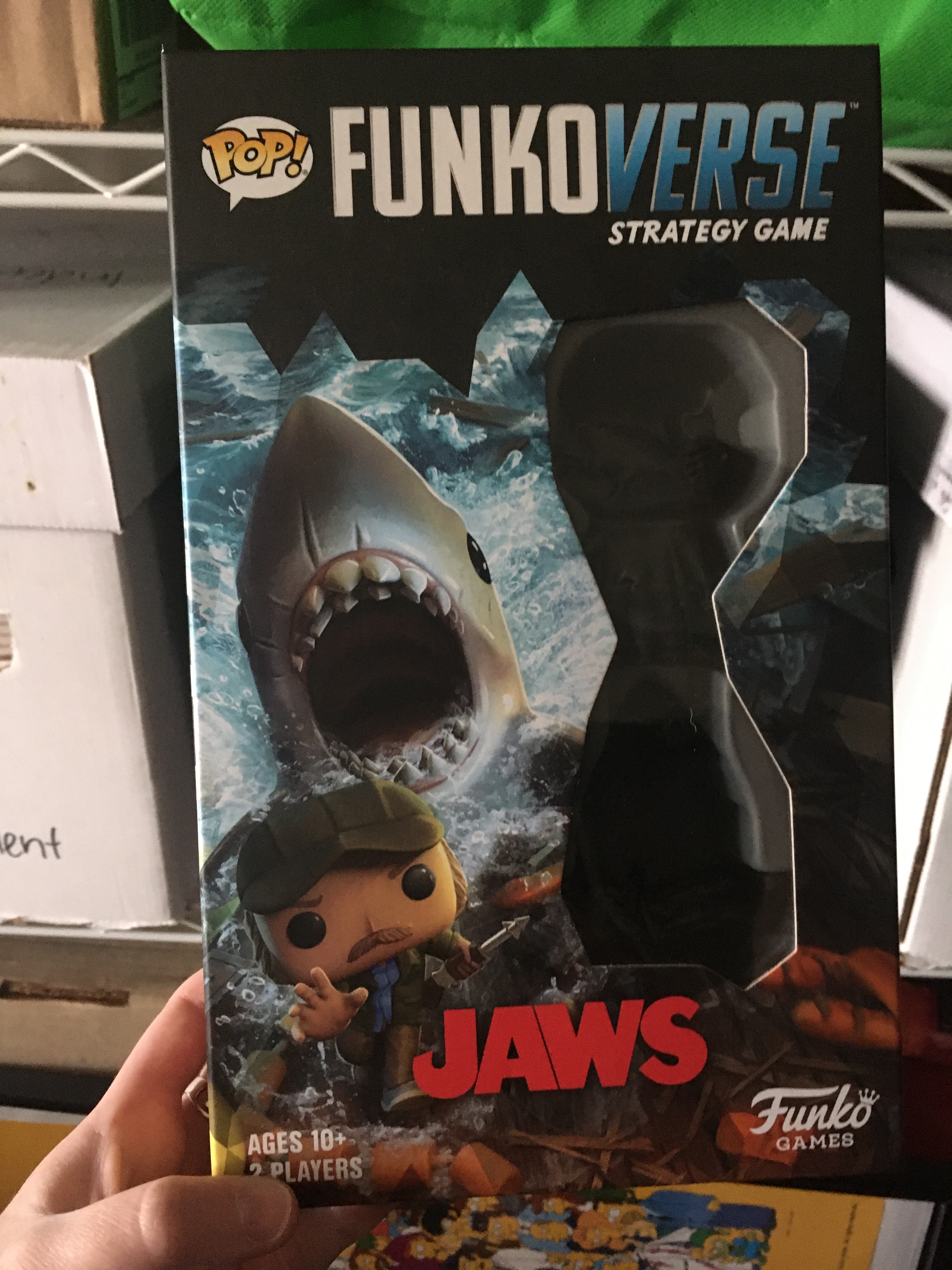

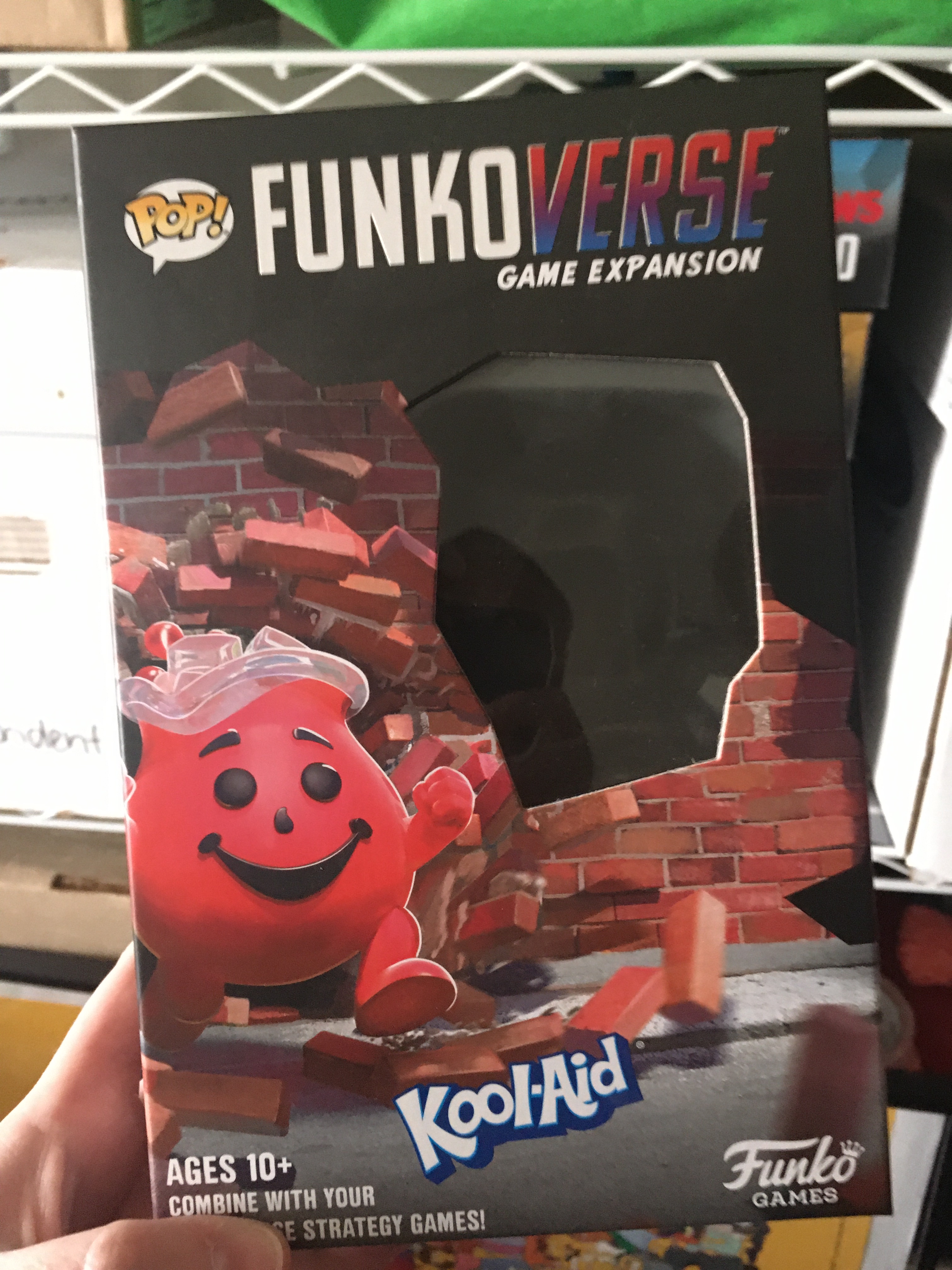

Expansions played: Harry Potter 100; Harry Potter 101; Jaws 100; Jurassic Park 100; Jurassic Park 101; DC Batman 100; Kool-Aid Man 100

Gist of the game: In a 2-player game, players choose up to 3 characters to play as a team against one another. Players place choose one of the two possible scenarios for their chosen map and then set up the map according to the scenario sheet, which will also specify the starting areas for each player. Players compete to win points, and the first player to cross the required points threshold (6 points if playing with 2 characters, 10 points if playing with 3) wins.

To play, each player chooses their characters and a single item (optional). Players receive the character card and any relevant status cards or tokens for their characters. Players take 2 ability tokens as specified on their character card. The map is set up as specified on the scenario card and player place their characters within their respective staring areas. Dice and point tokens are placed where both players can access them.

The game is played across rounds. Once every character has taken a turn, the round ends. To take a turn, players choose a character who has not yet taken a turn that round and take up to 2 actions with the character. The same action cannot be taken twice (we did not play according to this rule because we forgot about it. If anything it made the game more lively, so we may just house rule that option in the future). Characters have a set of basic actions: move up to 2 squares in any direction, including diagonally; challenge an adjacent rival; stand up an adjacent ally that has been knocked down; and interact with points tokens on the map. There are also a few special actions: use a character’s ability by spending an ability token; or use an item. If a character has been knocked down, the only thing they can do is use 2 actions to stand back up. Once the character’s turn is over, the player places an exhaustion token on the character card, and that character cannot take another turn in the current round. Play then passes to the next player, who repeats the process.

When all characters have been exhausted, the round ends. Players shift everything on their cooldown track down one number. Things that shift off the track (to below 1) return to play: characters return to their starting area, ability tokens are replenished, and item cards are returned to the character with the item. Exhausted tokens are removed from character cards, and the first player token passes to the next player. Players compare their scores at the end of the round. If the scores are tied, play continues until one player has more points at the end of the round. When that happens, that player wins.

To move a character, it can move to an adjacent or diagonal space, but not through rivals or obstructions.

Challenges allow characters to knock each other down and knock each other out. Every character can challenge an adjacent rival. When issuing a challenge, the player rolls 2 dice. When using an ability to issue a challenge, the player rolls the number of dice specified on their character card. The other player rolls a number of dice equal to their defense score. Th dice have faces for fighting an defense. If the challenging player has more successes, they win the challenge and the rival is knocked down, signified by literally placing the character’s Funko on its back. If a knocked down character is challenged and loses, the character is knocked out, removed from the map, and placed on the 1 space on the player’s cooldown track.

To use an ability, a character spends the appropriate ability token and places it on the cooldown track on the value specified on the character card.

Items can serve as abilities or traits, and some items have a challenge action associated with them.

There are lots of specific rules concerning line of sight and obstructions, but basically a character has to be able to see the rival to challenge it; characters can move through allies but not rivals to their final destination; and cannot move through obstructions, but rather has to travel around them.

Color commentary: This game is designed with near perfect modularity, such that any characters can be played in combination and on any map. I assume items are also perfectly portable, but we have not tried playing with items yet. There are only 4 scenarios total, repeated across the various map boards, but the luck component to challenges and the sheer number of possibilities means that there’s a lot of potential for replayability. I do think it’s a little disappointing that there are only 4 scenarios that just get repeated, but it seems like it might also be possible to create additional scenarios if you wanted.

In essence, this is a tactical combat game with delightful miniatures. Perhaps as importantly, everything can be organized into nifty containers from Harbor Freight (ok… maps are in a large post office mailing box while I figure out a better solution for them). The large number of possible characters and all the tokens to sift through made the first set of games kind of a hassle to set up. We spent a chunk of yesterday afternoon organizing everything, and setup was much easier.

The tactical combat part is important to note, because there were multiple pages spent on line of sight, and combat is resolved strictly through dice. It reminded me a bit of Memoir ’44 in that respect. I’ve seen chatter on board game discussion forums declaring that Unmatched and Funkoverse are in no way similar to each other, but I would argue they are. Combat is resolved differently, sure, but both games have: a) perfect modularity; b) a basic goal (points in Funkoverse, which can be gained in part through knocking characters out; defeating the hero in Unmatched); c) maps; d) nifty figures; e) high player interaction since victory can only really be gained by doing things to the other player’s characters. I suppose you could win a Funkoverse game by just acquiring points tokens over time, but that seems an unrealistic scenario, and unlikely that the other player would be following the same strategy. So, again, the combat mechanisms are different (cards for Unmatched, dice for Funkoverse), but the spirit of the games feels similar to me, which isn’t a bad thing.

Furthermore, I did thoroughly enjoy going shopping at Harbor Freight for our containers and then packing everything into them, as evidenced by the pictures above which showcase my handiwork. I am soliciting suggestions for map/cooldown track/booklet storage, so let me know if you have any ideas. The big challenge with the maps is that they come in two different sizes. Most of them are fairly narrow, but two of the base boxes came with wider maps, which eliminates a number of possible solutions. The search will continue.

On our first day of playing, we stuck with just the first couple Harry Potter sets. I played Voldemort, Draco Malfoy, and Belatrix LeStrange. M played Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, and Hermione Granger on the Forbidden Forest map. We played both possible scenarios for that map, “Leaders” and “Control.” “Control” had a definite 1st player advantage because once you move into a new control area, you can place a control token for free, but if you move into a location that already has a token, you have to use an action to flip it. So the first player can control an area on their very first turn, earning both a point at the end of the round for controlling any areas as well as a point for controlling the most areas, whereas the absolute earliest the second player would be able to flip a token would be in the 2nd round. The “Leaders” scenario sees players earn points for knocking each other’s characters out, thus favoring an aggressive strategy. Upon a debriefing of why I lost so miserably yesterday, M informed me that I seem to lack the killer spirit, and have basically lost every game scenario we’ve ever played that favors aggression as the dominant strategy. I’ll let him explain more below.

For our third game, we embraced the modularity. I played the Shark from Jaws and the T-Rex and Raptor from Jurassic Park. M played Batman, Hermione, and the Kool-Aid Man. We played on the South Beach map from the Jaws pack. For this map, we played the “Flags” scenario, which I won, despite M’s hard turn toward attrition less than halfway through the game, where he no longer tried to make it to my flag, and instead spent all his energy thwarting my attempts to be adjacent to his flag at the end of the round (moving your character from by the flag back to your starting area earned the most points out of the points-earning options).

Thoughts from M: Look. I’m going to say it’s a fun game, and you’re going to say I say that all the time, and I’m going say that you’re right, but also that if a game isn’t fun, what’s the point? Like most combat games, it rewards aggression, which is especially true when you have two players (I’ll comment more on Petra’s soft heart in a moment). The “Control” scenario we played rewarded rent-seeking, which I exploited whole-heartedly, but wasn’t as much fun as the more combat-based interactions we had in the “Leaders” scenario, where you basically the only way to earn points (aside from points tokens) was by knocking out each other’s characters.

As we were playing with the Harry Potter characters on our first couple run-throughs, I got to thinking. Why was JK Rowling so determined to relate the events of the books to muggle years? I mean, a huge deal is made about the final Battle for Hogwarts being in 1998. That naturally raises the question of what impact the rise of Tony Blair had on the wizarding world. Did Cool Britannia inspire Harry and friends? And then later did Blair did try to recruit them Wizards to fight in the War on Terror? I bet that would have really impressed Bush. And then were Death Eaters sent to Gitmo? So many unanswered questions. Someone should write a book about it. (Actually I did some research into this topic and found out that Voldemort was behind the death of Princess Diana, and now the entire Harry Potter universe must be viewed in a new light with me wondering if Dobby was tragically manipulated into fighting on the side of evil. Was he really a free elf? Was he?)

Now, in terms of Petra’s infinitely exploitable weakness… I mean, kind heartedness, I’ve noticed a trend in games like BarBEARian Battlegrounds and Unmatched, that when the situation calls for aggression as the only possible way to avoid losing by attrition, she will quite doggedly embrace getting ground down rather than engaging in aggression herself. And for that, I love her, both because it lets me win games and because she’s probably a better person than me.

M’s rating: 6/10

Petra’s rating: 6/10